A Draining City Experience

Homelessness, glitz, slums, and a violent history make Buenos Aires an exhausting and contradictory city

October 2018

We take the low-cost airline Fly Bondi from Bariloche to Buenos Aires. Low cost airlines are sprouting up throughout much of Latin America and a sign that a middle class is taking root. Even Mexico, where roughly half the population is quite poor, has a bevy of low-cost carriers.

As we board, I am reminded of the young 20-something year-old women we met in a hostel in Bariloche who were spending a weekend away from the capital. Both work in marketing firms and flew Fly Bondi for their getaway. Although Argentina is perpetually in an economic crisis, there are people with a little extra cash to run away for a weekend. Even if they do not have the cash handy, they can do what many in Latin America do and pay for their tickets in cuotas (Spanish) or parcelas (Portugese) over multiple months. This means the cost will appear in equal payments for months on successive credit card bills. This is a clever way to stretch purchasing power in countries where average incomes come nowhere near those of Europe or North America.

The Argentine consumer, however, is limited by the Argentine merchant who does not take credit or whose machine is always “broken”. An Uber says he loves vacationing in Brazil because everywhere takes credit cards. He can go on vacation without having the money handy. Brazil is indeed a very popular destination for Argentines in the summer months.

We arrive in Buenos Aires and take an Uber to our AirBnB in the fashionable Palermo neighborhood. The boulevards are wide and grande and look very Parisians. The parks are leafy and the subway connects the city very well.

The ATMs in the neighborhood, however, are filled with homeless people sleeping. I think twice before going into an enclosure with 10 homeless people to withdraw a few hundred dollars.

The homeless population is truly staggering throughout the city. Full families and whatever possessions they can carry, along with their pets, are living in the streets. Argentina’s 2018 crisis has exacerbated an already difficult homeless situation.

Given that the homeless are scattered throughout well-off neighborhoods, Buenos Aires’ poverty looks similar to that in San Francisco and Seattle. However, those in low-income areas many lack basic services and dignified living conditions. In an Uber to an outlying area, we pass slums without paved streets and homes constructed of metal scraps. Many of these neighborhoods lack access to drinking water and sewage treatment. Just like in San Martin, a little outside the glitzy, developed city core the level of poverty is striking. National statistics tell a dire story as well. In 2020, 40 percent of Argentina lives in poverty while in 2019 around 35 percent did.

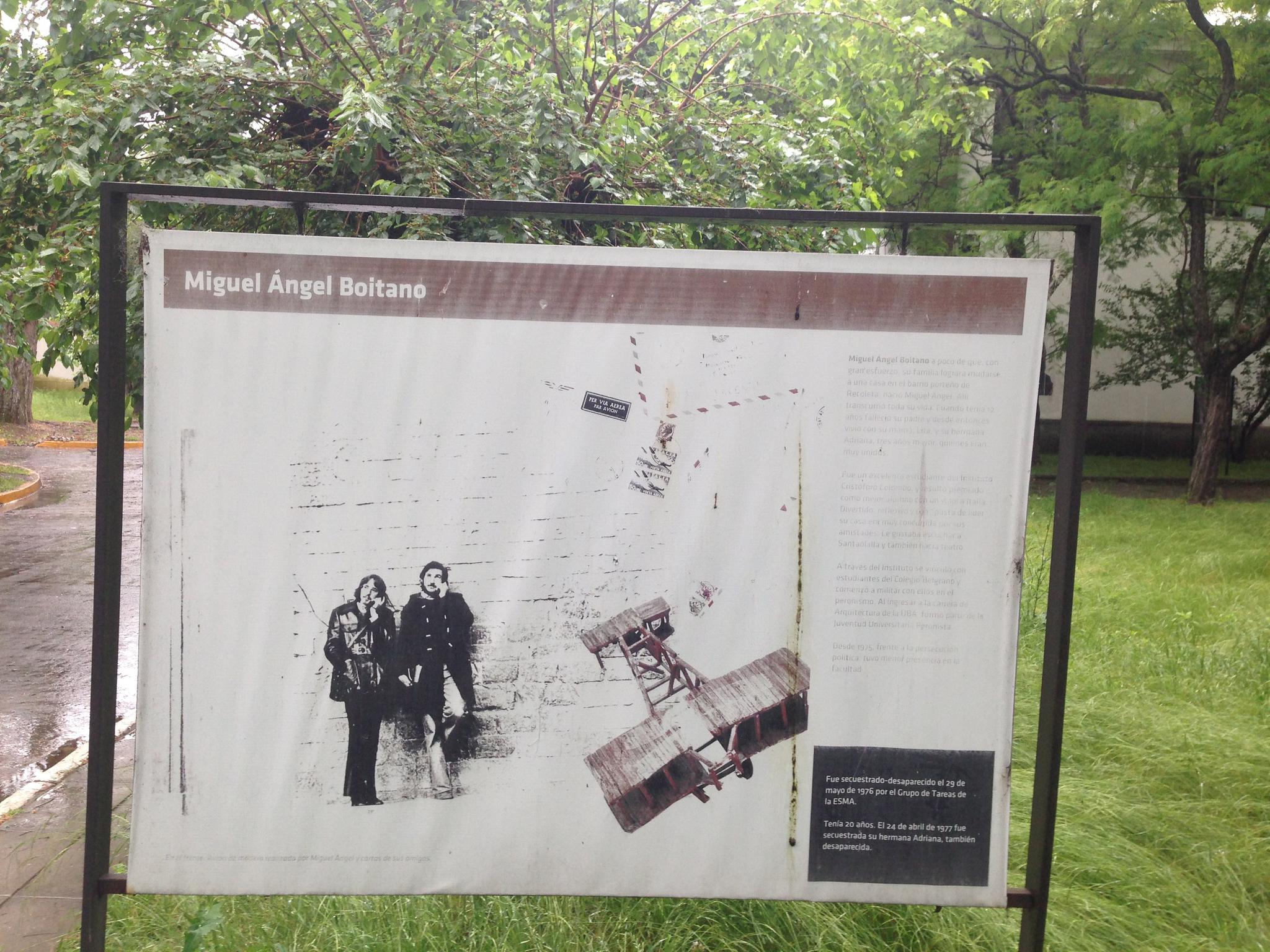

We pass the slums on our way to the Dirty War Memorial Museum which is another symbol of Argentina’s difficult past and present. The Dirty War was the period of the U.S.-sponsored, right-wing dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s in Argentina where thousands disappeared due as a result of state violence. The Argentine experience is very similar to the Chilean, Uruguayan, Central American and Brazilian.

The museum itself is dilapidated. While free to all, the lawns are overgrown and the plaques and signs that tell the victims’ stories and commemorate their lives are all fading. Perhaps it is too apt of a metaphor. The further away a society goes from an event the more it fades from their memory.

The buildings are the places where prisoners were held and tortured. We tour the torture chambers and read and hear the stories of the people who died in the very places we stand. It is chilling.

I remember my conversation with an Argentine sociologist in San Martin. I asked how Argentines refer to the Dirty War. She replied it is “state terrorism.” She seemed shocked that I even called it a “war.” The word “war”, perhaps, was too soft of a term for what occurred.

War implies some sort of relative equality between sides. This was where state machinery was brutally used against individuals and small groups to imprison, torture and kill. Babies lost their parents and were raised by other families without knowing what happened to their parents. Terrorism does sound more appropriate.

The next day we take a walking tour of the major sites in the center. Before we start the tour, we go to a very crowded market in the center. Everything is for sale. We will see sprawling, kilometers long markets like these in Brazil and Italy as well. Even though it is Sunday in a Catholic nation the city is bustling.

The question is how Catholic is Argentina. An Uber driver said that he is in a decade-long relationship with a woman, they live together, and have children. “Weddings cost too much money. I’d rather spend the money to go on vacation than have a formal wedding,” he remarks.

Other Argentines to whom I speak affirm that this practice was common and the monetary reasons were the same. I start to feel that asking people if they were married or wanting to get married was a dumb question as the answer was always the same. Perhaps not coincidentally, all younger Argentines I meet say they do not go to church. Official statistics show that Catholics are now under two-thirds of the population. Gay marriage is also legal.

Argentina’s southern European Catholic heritage, however, is present both in the churches throughout the city and the graveyard where our Sunday walking tour ends. As in all of Latin America and southern Europe, the graveyard is an ostentatious display. Massive tombs -- some as large as a car garage -- are colorfully and intricately decorated.

The Catholic Church’s influence is still strong in matters of abortion rights. Abortion is still illegal in Argentina and in mid-2018 massive protests for and against an ultimately failed law to legalize abortion polarized the nation. The Pope is Argentinian. Tradition may wane but it is slow to die.

Although it is only mid-spring, the city is as hot as a European city in summer time. Its Parisian-style sidewalks are on the verge of steaming and the cafes all have outdoor seating next to the street.

As we sip espressos outside a cafe, we witness a young man get chased down, slammed to the street, and aggressively arrested by the police. The entire street stops in its tracks to watch the chase and apprehension. The suspect is a main character in his own nightmare. The aggressive apprehension and humiliation of a man shakes me and I cannot shake the scene from my mind for days.

After a few days in Buenos Aires’ heat, history and disquieting present, I am ready to move on toward Uruguay. Although I had many good conversations with a wide-range of people, my eleven days in Argentina only scratched the surface of one of the geographically largest nations in the world. We did not venture deep into the lives of Argentines like I had done in most other countries we visited. While most conversations were one offs with Uber drivers, hostel workers, and hostel guests which revealed quite a bit about the Argentine mindset, struggles, and contradictions. Just talking to people -- literally everyone you encounter and who is willing to speak with you -- provides a wealth of information about how a society thinks and functions.