Pinochet's Ghosts

The legacy of a dictatorship still looms large in Chile

This is the first in a three-part series on Chile's recent past, present, and future. The second piece is Changing Toward the Modern and Traditional and the third Debts, Hard Work, and Lazy People.

September 2018

We leave Lima by airplane in mid-September to Santiago. Although Peru and Chile border each other, the flight between capitals is four and a half hours (think Seattle to Houston). The geographic distance is vast. The cultural difference appears equally so.

Arriving in Santiago from Lima feels like you have just landed in Germany from South America. The cars are newer and larger than in Peru, Ecuador and Colombia. In the Andean nations, super compact cars not even sold in the United States were common. In Chile, newer full-size Renault sedans appear to be the norm.

In Santiago the police (or carabineros in Chile) have a distinctly German feel, too. The carabineros have neat, crisp green uniforms modeled on the German police.

The military, too, has German elements. Our first full day in Santiago is Independence Day. There is a massive military parade that includes a military air show. The uniforms and helmets resemble the German military. The nationalist display may as well be occurring in the Third Reich.

The architecture and layout of Santiago has a distinct German feel as well. The streets are logical and grid-like. The apartment buildings are closely constructed together. There are well-maintained parks throughout the city. Trash on the streets is almost non-existent. Everything is a stark contrast to Chile’s neighbor Peru.

Prior to arriving in Chile, I frequently heard that it was quite distinct from most Latin American nations. It is the only nation in Latin America whose citizens do not need a visa to visit the United States. At roughly 15,000 USD, its GDP per capita is the second highest in the region after Uruguay. It is often hailed as the Latin American economic success story.

Peel back the layers, however, and the picture is nuanced. The minimum wage is 427 dollars a month, barely above Peru’s. The level of inequality is one of the worst in the region. This explains how a country can have a high GDP per capita but have such a low minimum wage.

The prices, however, are significantly higher than other nations in the region. Using a public restroom runs, on average, about 1 dollar. A meal in a casual restaurant is between 8 and 10 dollars, about double the price of Peru.

The retirement system was privatized during the reign of Agosto Pinochet with the help of right-wing North American economist Milton Friedman and his “Chicago Boys” (the name by which Friedman’s economic team is referred to in Chile). While in Chile, I read reports that the system is wholly inadequate for most. Juan, who as a self-employed farmer can opt out of the retirement system, considers the system a total rip-off for the average person. “Fees are high, you have little control over your investments, and no one gets out of it what they put in,” he tells me. He opts out. Many point out that the pensions are woefully inadequate to live on, and the government is seeking to reform the system.

The privatization of the pension system is the dream that George W. Bush and Paul Ryan held for U.S. Social Security. Fortunately for North Americans, the United States is a democracy and the privatization did not pass. Unfortunately for Chile, Friedman’s “Chicago Boys” had a ruthless dictator to implement their vision.

The neoliberal paradise of Chile also outlawed labor unions. To this day, three decades after Pinochet, labor union participation is only about 20 percent. Moreover, cooperatives were outlawed until a couple years ago as part of anti-union laws begun under Pinochet.

Without cooperatives, rural farmers lacked bargaining power with supermarket chains and transportation companies. This also stifled competition and encouraged monopoly, according to Joel whom I meet on the island of Chiloe. Joel, now 65 and retired, worked for many years in the tourism and transportation industry on the agricultural island.

Joel suffers from a serious blood disease, MDS. He is also the victim of a neo-liberal health system. MDS is only treatable with azacitidine. Azacitidine is an extremely expensive drug that would run in the thousands of dollars per month if Joel bought it over the counter. His government insurance paid for azacitidine only until he was 65. Perversely, Chile’s government health insurance ends coverage for certain medications like azacitidine when one turns 65. Currently cut off, he is in a crisis about how to procure the drug.

While it is inhumane that the United States does not universally cover people until they are 65, it at least takes care of its elderly. In Chile, some spend their final years in poverty without access to necessary medicine.

Every North American newspaper will remind you, however, that Chile is the economic success story of Latin America. The North American press rarely notes the cost of this success. As in any good neoliberal nation with a hangover from a dictatorship, many of Chile’s people live deeply insecure lives.

Chile has one of the highest depression rates in Latin America, an Uber driver in Santiago tells me. His father and grandfather were afflicted by deep depression and anxiety. He adds that people do not trust each other and have an every person for themselves mentality. Both are symptoms of the dictatorship.

According to our driver, during the dictatorship friends ratted on friends and relatives on relatives. The consequence for those ratted on was torture or death. Those who ratted were left with guilt. Everyone knew someone who disappeared. Thanks to Chile’s neoliberal project, most state economic support disappeared simultaneously.

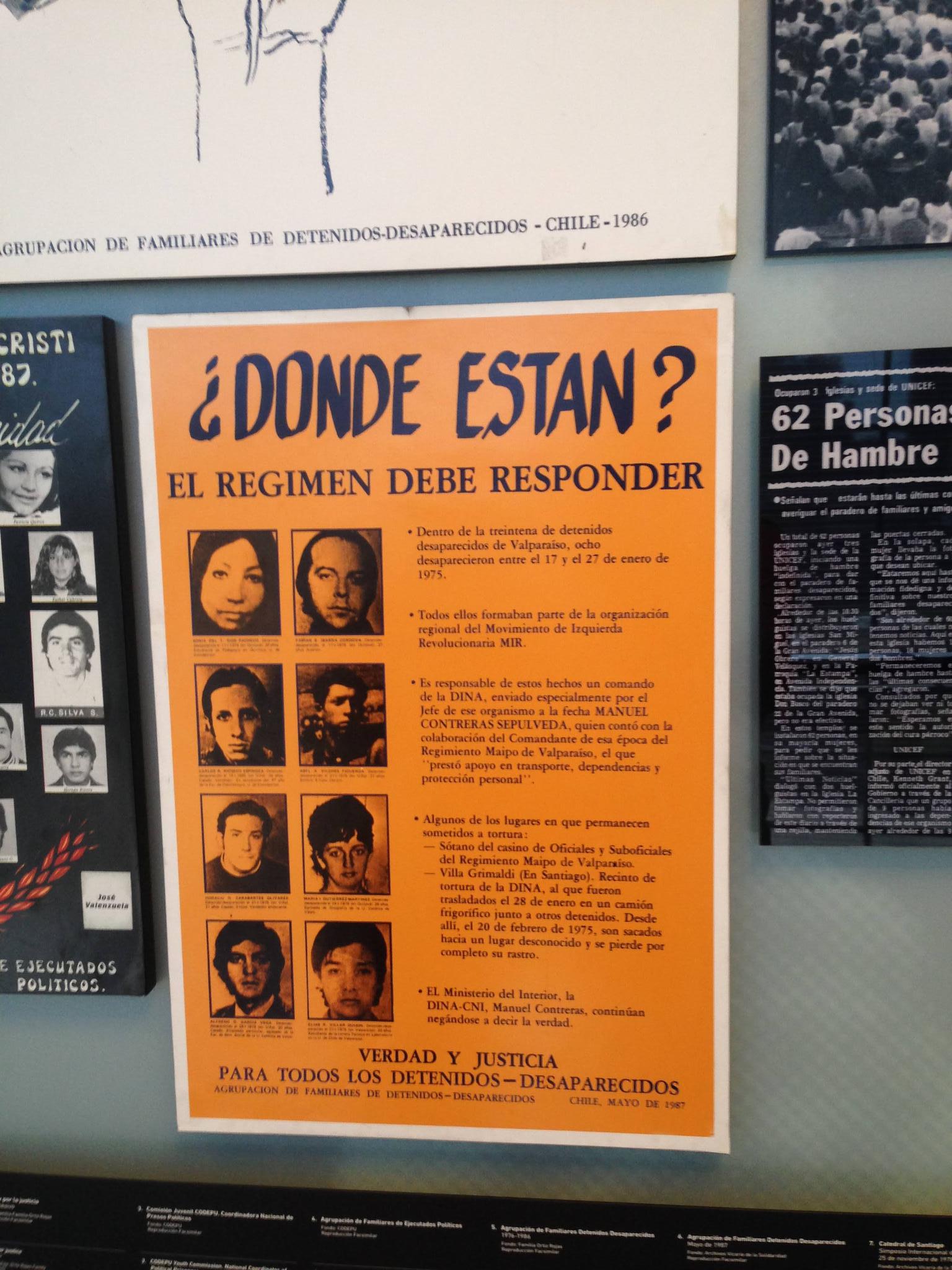

Chile’s dictatorship is considered the most brutal in a region of brutal dictatorships. Jimena, a human rights lawyer and law professor, documented Pinochet’s crimes with the help of Catholic priests. Jimena’s best friend and husband were murdered by Pinochet’s henchmen after the 1973 coup that brought him to power.

Jimena’s friend’s mother was told that if she did not reveal the hiding place of her daughter and son-in-law, Jimena’s friend’s baby would be killed instead. The friend’s mother gave up the hiding spot and the baby lived.

Years later, the grown baby asked Jimena if her mother loved her. “How do you answer a question like that?” Jimena asks with tears running down her cheeks.

Jimena still works with family members who seek justice for the crimes of the dictatorship. In order to receive benefits like life insurance, family members need a death certificate. In many cases, Jimena says the state will not provide the death certificate because there is no body. “It is the same state that dumped the bodies in the sea!” she exclaims. “They know damn well what happened but they do not care about making amends!”

Jimena describes Chile as a contradiction. The exterior looks orderly, civilized, and European. The inner core, however, is dark, insecure, and violent.

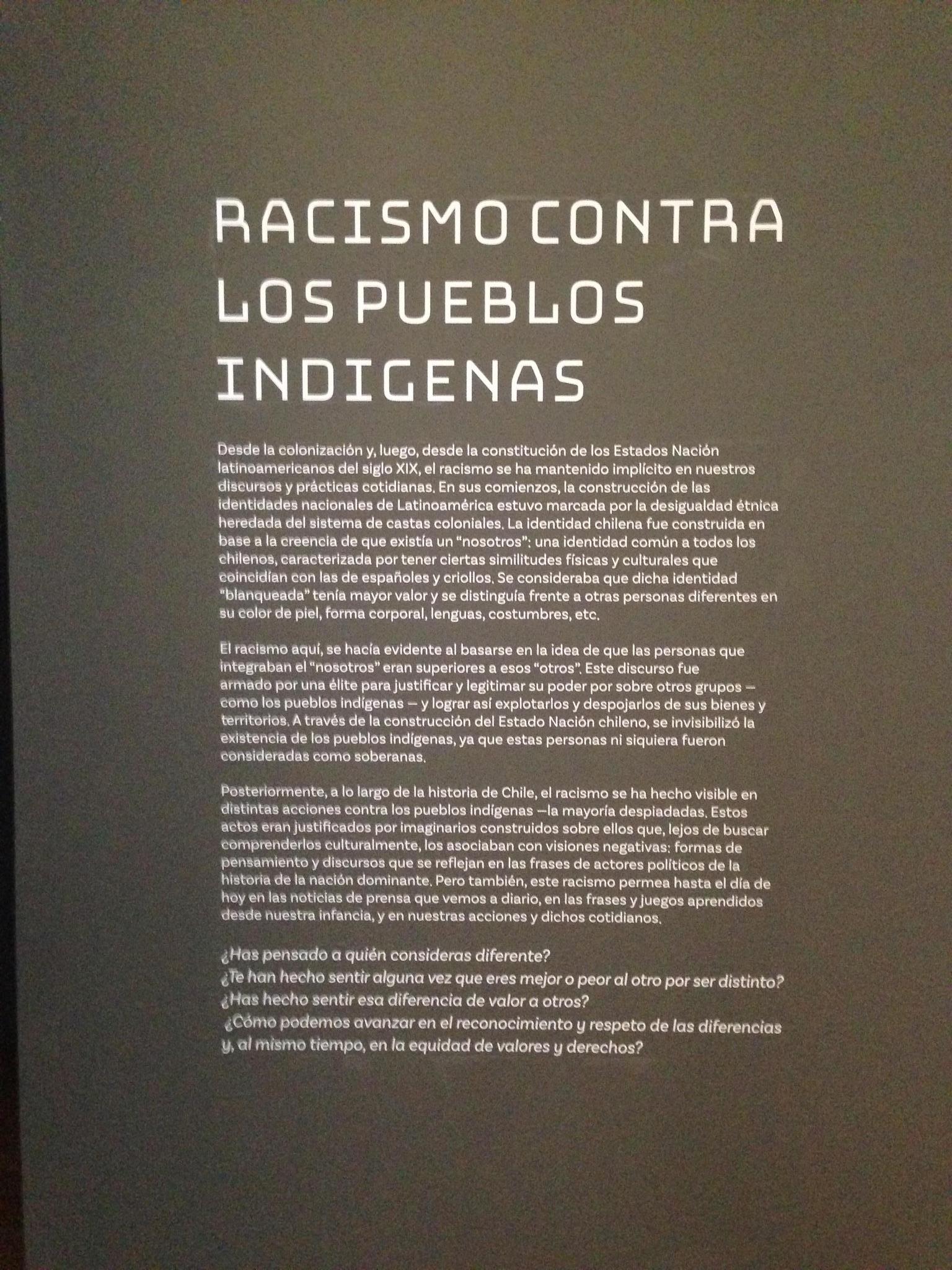

In addition to the scars of the dictatorship, there is ferocious racism toward brown and indigenous people. Jimena tells the story of a Peruvian maid who had her head slammed against a bathtub by her Chilean boss, knocking out her front teeth. “The racism toward the indigenous is terrible in Chile,” Jimena states.

Jimena also says that to be indigenous in Chile means you will face major discrimination in finding good work. Top law students she has taught who are indigenous have had trouble finding work.

Chile, despite Santiago’s European look, is a mestizo-majority nation (mestizo meaning mixed between European and indigenous). The majority in Santiago are comparatively lighter than in Peru but significantly darker than in Argentina or Uruguay. Moreover, there are rural areas I visit that are heavily indigenous.

In contrast to indigenous life in the cities, multiple Santiagans tell me that being indigenous can bring significant benefits in the countryside. I leave Santiago after a few days and head south to the Mapuche Zone to see if this is true. The Mapuche are one of the main indigenous groups in Chile. I will work on a farm there before heading to another indigenous farm on Chiloe Island on the edge of Patagonia. Recently gained rights and recognition, along with the ability to be self-sufficient and not depend on employers who discriminate, means that in principle the indigenous can build their own worlds and thrive. I will see if this is a reality in the next, forthcoming piece on Chile.

Some of the names of the people featured were changed to protect their privacy.

0 Comments Add a Comment?