Is Mexican Religion in Decline?

The first in a three-part series on Mexican belief systems. Part 2 addresses Mexican beliefs in ghosts and spirits and part 3 address witchcraft, spiritual healers and death cults.

A first-person look at whether Mexicans remain faithful

April 2023

Mexico City

“The younger generation has very little faith anymore,” laments our driver in Mexico City. “They mostly meet their needs through other things. My kids never want to go to church and don’t see the point. My husband rarely goes to church, either. I am the only person in my family of four who goes to church regularly and with true faith.”

“I, too, am faithful but less faithful than my parents’ generation,” she continues, a sad tone of loss in her voice. “For example, every year my father makes a pilgrimage to Virgen de Juquila in the state of Oaxaca. This year, I made the journey but it was the first time in many years. I went with my whole family to ask the Virgen to look after my health.” (Earlier in our conversation, our driver revealed she is fighting bone cancer.)

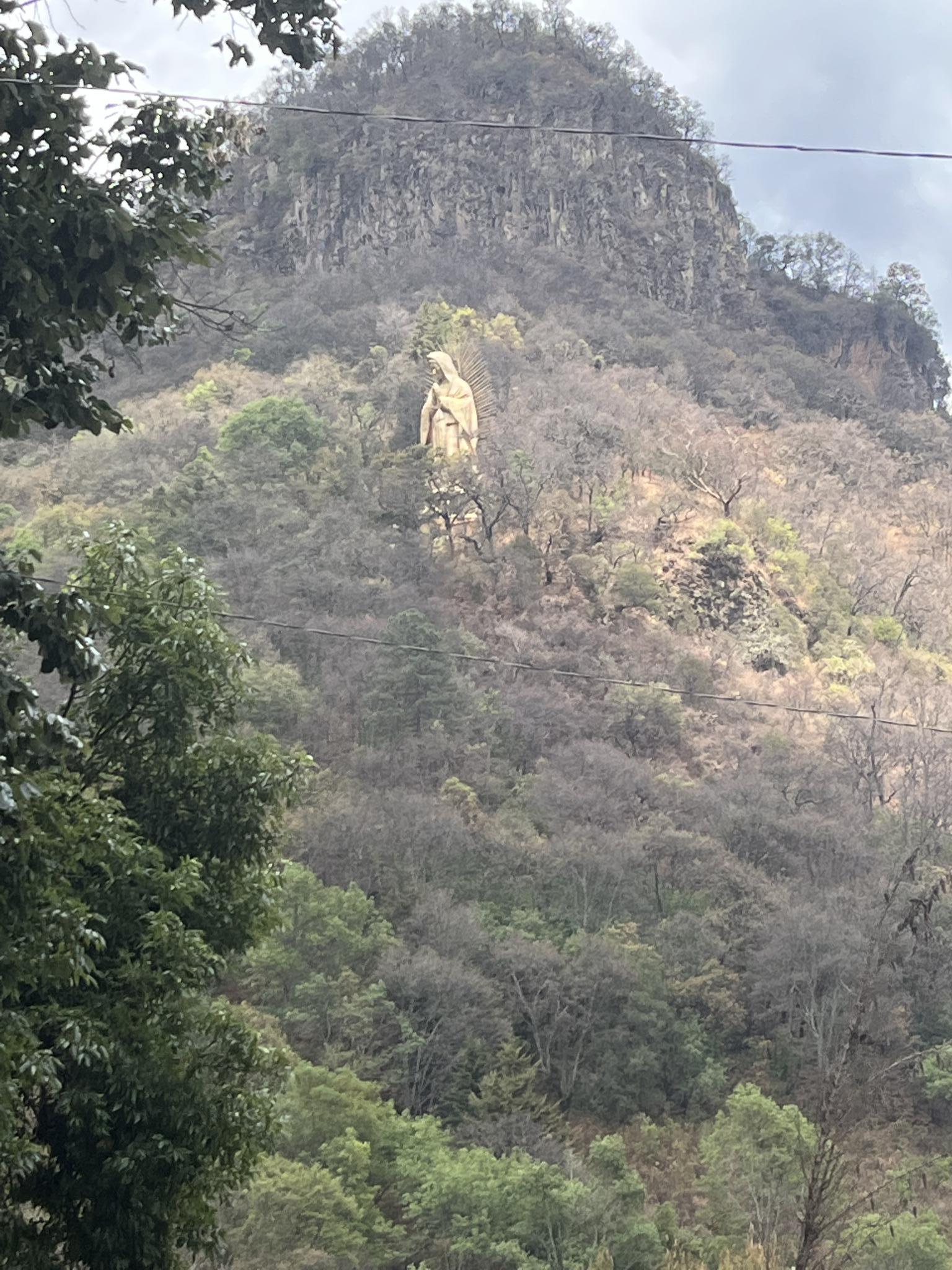

Mexico is rightly known as a place of great faith that follows a mix of European Catholic and indigenous beliefs. There are many pilgrimage sites throughout Mexico (many of which are statues of a Virgen).

While driving near the Virgen de Chalma, a pilgrimage site in the State of Mexico, every few hundred meters there are signs that say “watch for pilgrims”. This implies many will walk long distances to arrive at the pilgrimage site. The road to the site is a steep, windy mountain road that would be difficult to walk even for someone in good shape.

While we do not see pilgrims walking on the road, we do see many arrive by car and bus to the site’s entrance. It was a Thursday, the week after Semana Santa, or Holy Week. As such, many people had already returned to work (schools, however, were still on break). No matter – the site is still bustling.

We are on our way to Malinalco, about 20 minutes away from Chalma. Like most towns in Mexico, there is a church in every neighborhood and a main cathedral in the center of town. Entering the main cathedral on a Thursday afternoon, there are about 10 people praying in the cathedral. It is peacefully still and quiet.

The people praying on Thursday afternoon are all older women. The faithful in Malinalco remind us of the previous Saturday, the day before Easter, in Mexico City. We popped our heads into a few services. Those in the pews were mostly an older crowd. If a church is sustained by the elderly, its days are numbered.

We return to the Malinalco cathedral midday Friday, and the faithful are again exclusively elderly. On Friday, however, we are accompanied by three Mexican friends in their 30s who arrived in Malinalco the night before. Two enter the cathedral and pray for about five minutes as we wait outside. One gives a donation as he leaves the sanctuary.

I ask one friend if he is a devout Catholic. He says that praying at the church is a way to honor and connect with his mother. His mother is a devout Catholic and when he is in a church it makes him feel closer to his mom. His mother always taught him there is a powerful God above humans. Praying in a church reminds him of the existence of a greater being.

“Do you go to Church regularly?” I ask.

“No, but when I do go occasionally, or spend time on a church’s ground, it is a way to connect with my mother and her faith,” he replies. “I prefer to follow my own spiritualism in my own way rather than following the Church.” This friend also wears a rosario, or cross, around his neck.

I ask my other friend who entered to pray if he is a devout Catholic. “No, but I am a spiritual person,” he responds. “We grew up with these traditions, and although I don’t go to church regularly, I do believe in a greater spirit.” Infrequently visiting the Church, for both friends, is a way to both express their spirituality and maintain a connection with their family and traditions.

In Mexico City, over dinner at a friend’s house, we hear stories about pilgrims who would walk for kilometers on their knees from one part of the city to the basilica of the Virgen de Guadalupe in the city’s north as a demonstration of their faith. This pilgrimage would often occur when people were asking for a specific blessing – help for a sick family member, for instance.

But this tradition is dying. “It is much rarer to see this type of pilgrimage,” say our hosts. In contrast to our driver -- who lamented the loss of faith in the country -- our hosts' tone is not sad but more of prideful. Look at the spiritual richness of our country, they seem to say. Even if it is not as strong as before, sparks of it remain strong.

Indeed, it is hard for all the sparks to die. Rituals and traditions are often religious. Schools and government offices take religious holidays. Baptisms and first communions are major family and community events. It is very common to see people of all ages wearing a rosario (cross) or a depiction of the Virgen de Guadalupe, the patroness of Mexico. On every block and inside many small businesses there are small shrines to the Virgen. In Iztalpapa, Mexico City, each Holy Week there is a reenactment of Jesus’ walk to crucifixion. A man trains for the physical challenge of walking a long distance with the cross and the crowds for the event are still large.

Although there are fewer young people becoming priests, the reasons are not simply because there are fewer believers. Being a priest in Mexico is dangerous as priests are often in the crosshairs of criminals. Given the corruption and abuse scandals of the church, priests are often viewed negatively by the younger generation. Yet some still choose the profession, even if numbers have dropped off.

Others may avoid the Catholic Church but remain Catholic in their identity. In 2000, 2010, and again in 2020, the Catholic Church has seen a roughly 5 percent decrease in their followers. While significant, 77 percent of Mexicans remained Catholic in 2020. Moreover, compared to the decline in other Latin American nations, the decline in Mexico is significantly smaller. Slightly over 11 percent of the total population identifies as a non-Catholic Christian, meaning that the total Christian population (Catholic and non-Catholic) is just shy of 90 percent.

The 77 percent Catholic number would include my friends who briefly prayed in Malinalco but who rarely attend mass. It also includes the driver who attends mass regularly. The 11 percent non-Catholic Christian number includes another driver we meet who works 6 days a week but always takes Sunday off to go to his Evangelical church. Being religious is more than just church attendance and donations in Mexico. It is a connection with a higher being and often a belief in the supernatural which is still strong with many – both young and old. Is belief in a higher being in relative decline? Perhaps, but in 2020 only 10.6 percent of Mexico says they have no religion at all, and over 23 percent of this 10.6 percent still believe in a higher power (and anecdotally I have yet to meet a Mexican who is an atheist, which is only 5.4 percent of the 10.6 percent of the non-religious).

A belief in the supernatural – ghosts, witchcraft, and other spirits – is alive and well in Mexico, often alongside Catholicism. This will be the subject of our next two articles on belief and faith in Mexico (please view here and here).