Witchcraft, Spiritual Healers, and a Death Cult in Mexico

The final in a three-part series on religion and beliefs in Mexico. In part 1 we asked whether Mexican religion is in decline and part 2 we examined Mexican beliefs in ghosts and spirits.

April 2023

“She only slept during the day for fear of evil spirits coming at night. She always had a bracelet that, if broken, she believed meant the end of her life. She also carried a head with her. She would take care of the head, giving it cigars and food. If one does not care for their head one could experience bad luck.”

“So this is ultimately a culture of fear?” I ask.

“Very much so. Fear of spirits, fear of the dead, fear of upsetting those with greater power,” responds Alberto.

Alberto is talking about a high level functionary of Mexico’s PRI, one of the country’s major political parties which ruled the country for the majority of the 20th century and again from 2012-2018. Alberto previously served as the assistant to the functionary, often accompanying her 24 hours a day.

Alberto says almost all PRI functionaries, including ex-president Peña Nieto, are followers of santería, a form of spirit worship and witchcraft. The presence of magic and spirit worship has a long, well-documented history in Mexican political culture where politicians form many different political parties ask for good luck for themselves and bad luck for their opponents.

People believe that if you leave santería you are doomed to bad luck. Alberto says those who follow santería often cite examples of people who have left and soon after fallen on difficult times. He says people think, “Better to stay and not take your chances.”

Alberto then emphasizes that the key to a belief in anything supernatural is just that — belief. Alberto’s own mother practices witchcraft, which he emphasizes is not for evil ends but for good. Rather than call her a bruja, or witch, Alberto insists that she is a curandera, or spiritual healer. The title of curandera evokes is less ambiguous whereas a witch could mean someone who practices for either good or bad.

Alberto says his mother emphasizes that without belief, however, the supernatural will not work. She also argues that supernatural power should be faith and belief-based and not something paid for. Many witches and curanderas charge for their work, he says, but his mother believes this negates the effect.

I ask Alberto if I can speak to his mother directly. “You can meet her as my friend, but don’t ask her about witchcraft or curanderas. This is something she keeps private and does not advertise. She does not want people making assumptions about the work she does, assuming it might be for evil. She only performs her work on those she knows. If you bring it up to her she will not be happy with you or me.”

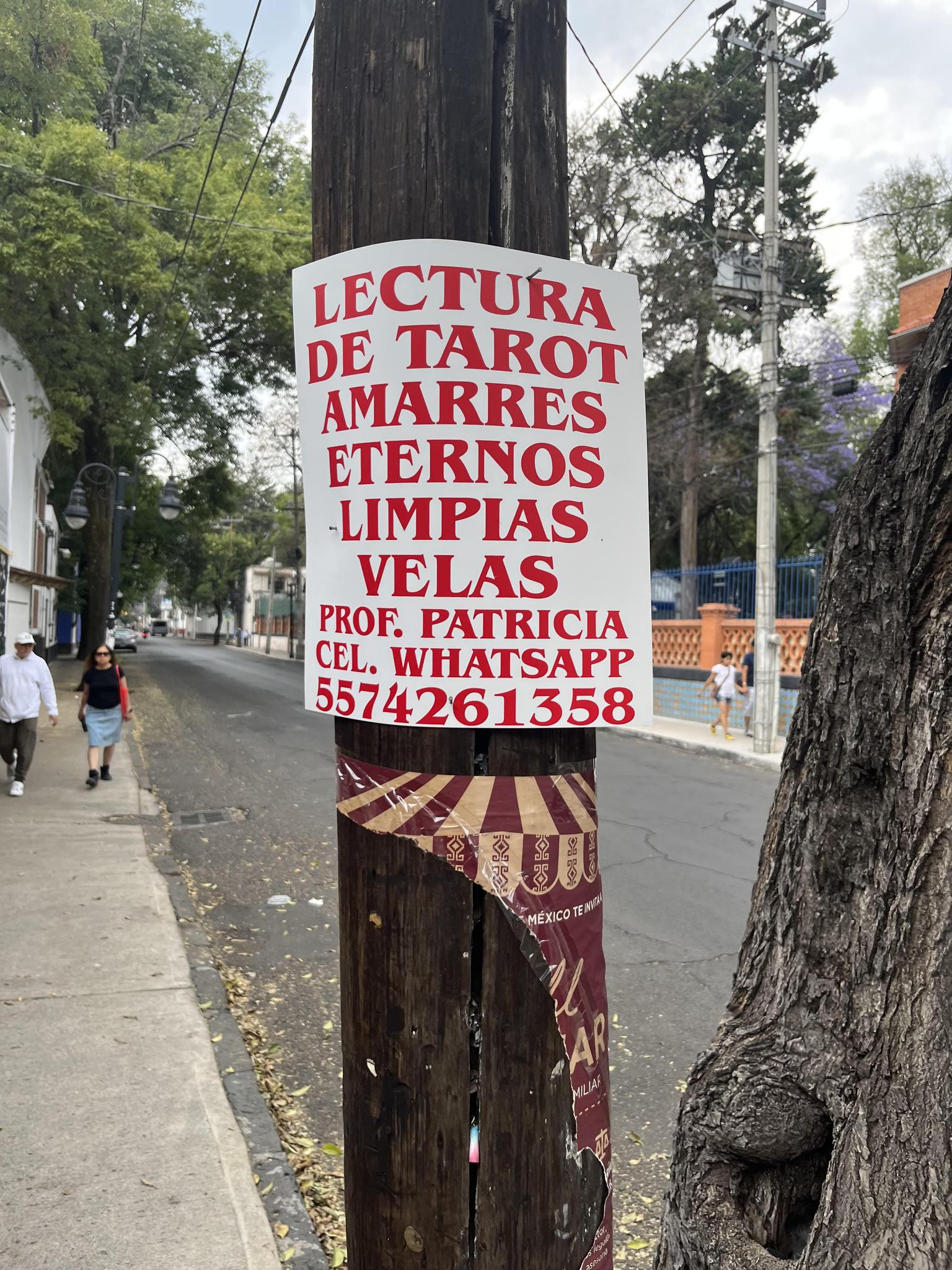

Alberto’s mom is in contrast to healers and witches who advertise their services. It is common to see paper ads stapled to light posts on city streets in Mexico’s cities. Some healers have risen to national fame. How many remain in the shadows, like Alberto’s mom, is impossible to know but it is likely large given the strength of the culture.

I ask Alberto if there is a contradiction in believing in the magical work of a curandera or witch and Catholicism. “My mom would say the belief in Jesus and God is always first but that the two can work together. Ultimately, if you have a strong belief in both, both can serve you well,” he replies.

Indeed, a belief in both the Church and other supernatural elements is common throughout Mexican culture. In the novel Tan lejos de Dios, a curandera faithfully attends mass while, at the same time, uses her healing powers to help those who seek her help. Many politicians who practice santería and visit witches also attend mass. Many of the pre-Spanish indigenous gods were converted into symbols representing elements of Christianity, such as the goddess Tonantzin representing the Virgen, the god Tláloc representing Jesus as a boy, and the main Aztec god Quetzalcoatl representing Jesus. Whether an individual is worshiping the indigenous gods, the Christian meanings, or a combination of the two is less important than the faith placed in the holy figure. (The Catholic Church is often vocally opposed to a belief in multiple faiths; no matter, people continue fusing beliefs.)

Ultimately, Mexican belief systems are a fusion of European, indigenous and African faith traditions. Traditions of witchcraft and spiritual healing have elements both the indigenous and African. While present throughout Mexico, the state of Veracruz is known as the center of many witchcraft and spiritual healing traditions. It is also one of the Mexican states where African traditions are very strong. Both the historically large presence of African slaves and its proximity to Cuba are major reasons. As is true throughout Mexico, many indigenous traditions remain vibrant in Veracruz. The combination makes the region a center for witchcraft and spiritual healing.

In addition to the belief in witchcraft and spiritual healing, a growing number of Mexicans believe in the Santa Muerte or death saint. Throughout Mexico there are representations of the Santa Muerte in petit chapels similar to those of the Virgen de Guadalupe. People pray to the Santa Muerte and, in some places, attend services led by a spiritual leader. As those interviewed by the BBC about the phenomenon of the Santa Muerte said, if one fervently believes in the Santa Muerte it is more likely their prayers will be answered.

Alberto tells me there is a representation of the Santa Muerte in the neighborhood where we are staying. He asks me if I would like to see it. I hesitate, think about it, and say no. It honestly scares me to see a representation of death. I half-seriously say, “I guess I recognize the power of the Santa Muerte.”

It dawns on me this is the common thread with all faiths. Only by recognizing the power of the Santa Muerte, santería, curanderas, witches or Catholicism does the power become real. The origin or contradiction of a faith does not matter to Mexicans — as long as one has faith, the faith will bring power.